Caractacus must have written his biography in exile in Rome, assuming he wrote one, but no copy of it has survived. So unfortunately, there was no translator involved here. I was first alerted to his extraordinary story in Graham Robb’s brilliant book The Ancient Paths, one of a growing number of historians and writers to start rethinking our pre-Roman past. But it was George Jowett’s strange and peculiar book The Drama of the Lost Disciples which got me thinking about Caractacus for the first time.

Jowett died in 1969 after a distinguished career as a boxer, publisher and planner in Canada. But the research behind the book, in the Vatican archives, is an equally important legacy. His argument was that, according to the archives, it wasn’t just Joseph of Arimathea who came to Britain in 38AD, as legend suggests – it was the Virgin Mary and many of the surviving disciples of Jesus who took refuge in Glastonbury that year, joined later by St Peter and St Paul. Jowett’s plea was that, given that the medieval church recognised this claim by giving British bishops precedence at the great councils of the Church – we ought to take this more seriously. Or at least as seriously as the flawed and compromised memories of Roman writers with axes to grind.

If this was right, Jowett suggested, then it may provide a different interpretation to the Roman invasion five years later. It may also be that Caractacus, as the archives suggest, was not a backward pagan type, but Christian king battling the pagan Romans and desperately trying to hold back their tide of brutality.

I have written Caractacus’ autobiography as if Jowett was right. As such, I am attempting to strike a small blow against a those generations of positivist scholars who identified with the Romans more than with their forebears defending our homeland – who regarded the invaders as ‘we’, and continue to try to subdue the real spirit of these islands ever since.Caractacus managed to stand alone for nearly nine years against the biggest and most sophisticated army in the known world.

Why did he? Because he was a civilised, intelligent man fighting the crass brutality of the Romans.

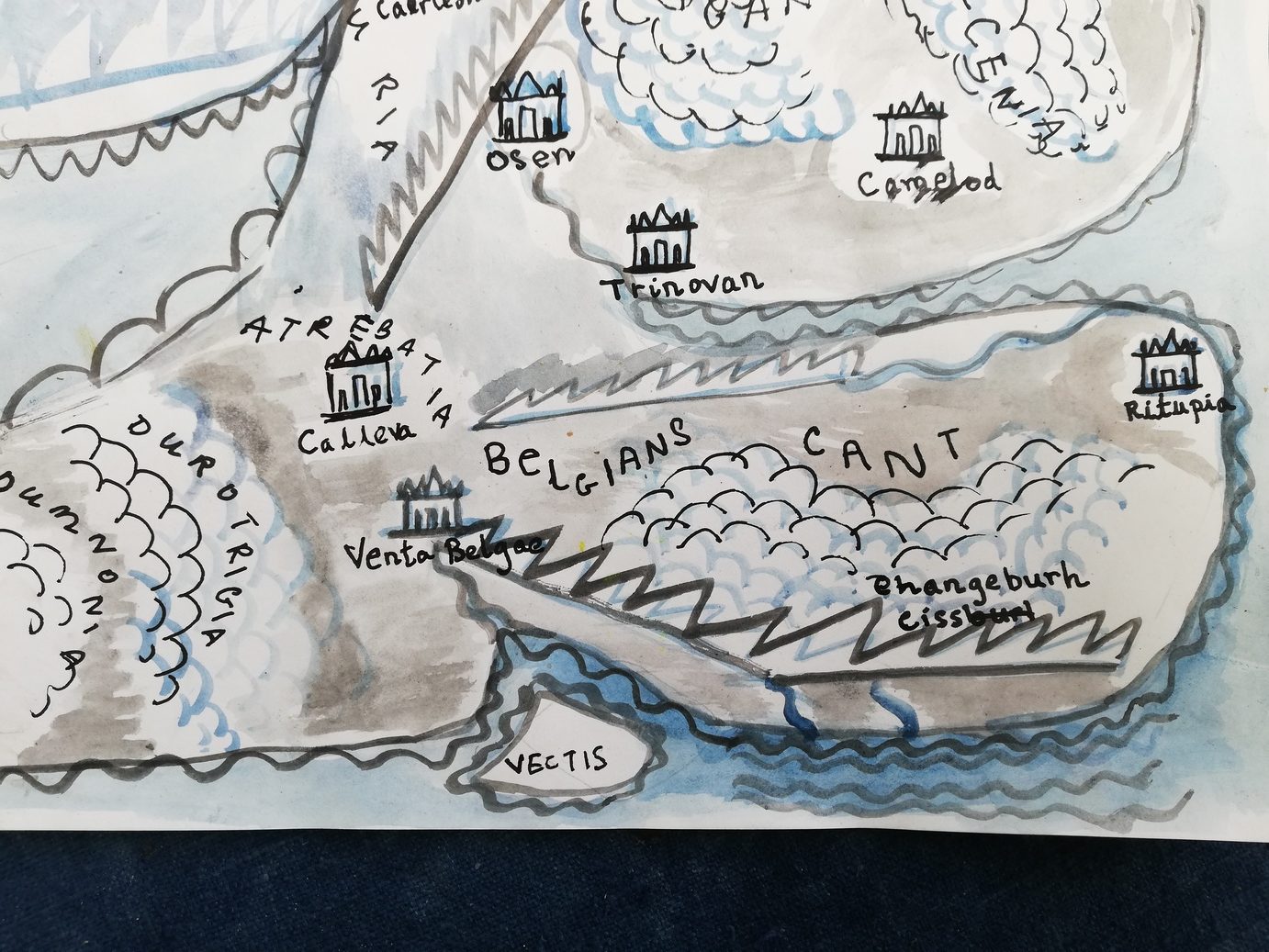

As such, we have had to rediscover the original names of people and places from the Roman documents which – just as one might expect from Italians to this day – tended to add a couple of syllables. So we have Togod not Togodubnus and Caradoc not Caractacus, or their father Cunobelin not Cunobelinus. We have also had to update the traditional Roman names for the so-called ‘tribes’ of Britain, aware that these were not so much tribes as separate and civilised nations. Hence Atrebatia, Brigantia, Siluria and Cant.

That may make it more difficult to interpret the place names, especially Trinovan, a shortening of the pre-Roman name for London, Trinovantum (at least according to Geoffrey of Monmouth). Some other place names, in case this is helpful. See also the map on above…

Brigantia Yorkshire and Northumberland

Caer Leon Caerleon

Calleva Silchester

Camelod Colchester (Latin: Camelodunum)

Cant Kent (as in Canterbury)

Castle of Maidens Maiden Castle, Dorset

Changeburh Chanctonbury Ring, Sussex

Ciss Cissbury Ring, Sussex

Dumnonia West Country (Cornwall and Devon)

Durnovaria Dorchester

Durotrigia Dorset

Gate Slinfold (means ‘gate’ in old Sussex dialect)

Home Hampstead

Icenia East Anglia (Norfolk and Sussex)

Isle of Apples Glastonbury (said to be the meaning of the word ‘Avalon’)

King’s Stone Kingston, Surrey

New Fields Chichester

Old Stone Steyning, Sussex

Osen Osney, Oxford (Graham Robb says this was considered to be the geographical centre of Britain)

Osenford Oxford

Ritupia Richborough, Kent

Siluria Gwent, Somerset and Gloucestershire

Trinovan London

Vectis Isle of Wight

Venta Belgae Winchester

Wood Town Bosham, Sussex